By Janet Unruh, Wilkes East neighbor

For nature lovers who hate to see the land scraped bare for housing developments, our best hope is that soon, it will no longer be profitable for developers to build new housing. This is our best hope because the city turns a deaf ear to the pleas of residents to stop, or at least reduce the size of new developments.

(If you don't see the full article below, Click "Here")

I recently attended an Early Neighborhood Notification (ENN) meeting for Kelly Creek, where a 149-lot housing development is planned. The city requires developers to have ENN meetings with the neighbors to show them the site plans and answer questions. However, as is generally the case, most of the residents’ questions can’t be answered because ENN meetings are held too early in the development process. Residents have virtually no influence over housing developments and no one from the city attends ENN meetings. Developers only want to know about things that could materially affect construction, like a nearby sinkhole. Like all the ENN meetings I’ve attended, residents expressed anger and frustration. They mentioned their love of trees and birds, their ire for traffic and parking problems, and concerns for kids' safety. One resident said the plan showed five narrow lots abutting the back of his property. The unresolved conflict between the neighbors and the developer reminded me of the “Rockwood Greenspace” at 270 NE 188th. In that case, neighbors campaigned to save 1.22 acres and 50 Douglas Firs, but the city thwarted their efforts[1].

Oregon law requires Portland Metro to forecast its population and employment growth every six years for the following 20 years. Metro must then distribute the projected need for housing among cities within the urban growth boundary[2]. For Gresham, the estimate in 2021 was 6,229 new housing units by 2040. 1,993 (32%) of these were expected to be townhouses. The state of Oregon has since updated the new total of units needed in Gresham by the year 2045 to 7,872[3].

According to city data, 1,641 acres of “vacant” land are available for development in Gresham. This includes not only greenfield lots but other scraps of open space, specifically large lots with houses or buildings that also have a half-acre or more of vacant land[4]. Based on these assumptions, the city says it has sufficient land to accommodate growth. Currently, there are 33 subdivisions under construction or in planning. This includes 2,141 total lots of which 1,138 (and potentially more) will be divided up for middle housing[5].

Middle housing includes duplexes, triplexes, quadplexes, townhouses, and cottage clusters[6]. House Bill 2001 (2019) and Senate Bill 458 (2021) required changes to the development code to allow middle housing to be built in areas formerly zoned for single-family homes with yard space. Because of this, townhouses are being built in those areas instead. Townhouses are favored by developers because the lot size minimum for townhouses is 16’ by 70’ or 1,120 square feet[7]. This results in tall, narrow housing units with shared side walls. The city manager has the power to approve these developments with minimal constraints[8]. Plans for street trees compete with utilities and little-to-no setbacks. Instead of planting trees, developers are allowed to pay into the tree fund.

Is Gresham going to need so much new housing? Most of Gresham’s in-migration occurred between 2010 and 2020[9], and currently, Gresham’s population is shrinking[10][11]. The outer areas of Gresham, such as Kelly Creek and Pleasant Valley, which are mainly rural, are fated to have more densification due in part to the intended effect of the metro boundary—to contain growth.

However, with so many units being built, and the population decreasing, the “inventory,” as it is called in real estate jargon, will increase. In other words, there will be too many units available for sale to support a sale price that would ensure profitability. At some point, a threshold will probably be crossed when it’s no longer profitable to build. A possible exception to this would be government subsidies that cover more of the costs of building. A slowdown in building developments will be marked by an increase in inventory (above 10%), price reductions, and the number of days on the market (over 15 is considered a lot).

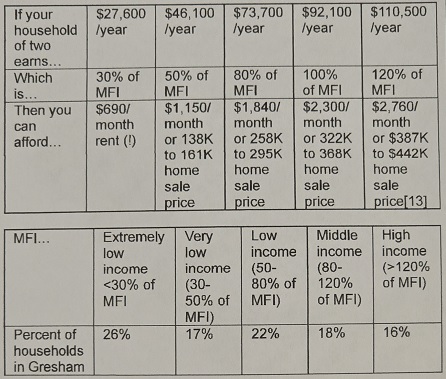

And then, there’s the matter of affordability. Government agencies use median family income (MFI), which is the halfway point between the highest income earner in the area to the lowest. As such, it is higher than the average income for a given area. However, it’s what we have to work with. The data below are from the Gresham Community Development Plan, Volume 1[12].

|

This means that 83% of our current residents can’t afford to buy a (town-) house. The cost of most (town-) houses in Gresham is over $400,000. Only high-income households, earning 120% or more of MFI can afford to buy them. Will Gresham attract enough high-income earners to absorb thousands of new $400,000-plus (town-) houses? |

Click to enlarge |

Essentially, the need for massive new housing developments is contraindicated by declining population and house prices that are out of reach for most people. Developers can’t wait forever to gain the profit they expect, and when losses accumulate, the building projects will stop.

I recently drove to Pleasant Valley, to SE Giese and SE 190th, to see the developments. I took a few pictures, like the one below.

|

Here’s an example of acres that have been cleared and flattened by excavators. In the distance, new houses are packed close together. Trees and nature have been wiped out. In their place, construction materials are assembled—materials such as acrylic, vinyl, particle board, and god-knows-what. |

|

In 100 years, the materials containing these unnatural chemicals will be hauled to landfills, where they will be rained on; the runoff will then find its way to creeks and rivers, and to living organisms.

I hope that one day we will have ways to break down massive amounts of garbage into their molecular components and recycle them. I’ve done some research in this area and found that the work has started, but it is not yet a priority in our for-profit economy.

As I came home to Wilkes East, I saw all the trees we have, and my weary mind was restored to a sense of appreciation and joy.